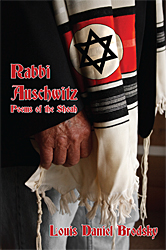

Rabbi Auschwitz

Poems of the Shoah

Paperback: 78 pp.

Published: 2010

Price: $15.95

BUY THE BOOK from Amazon.com

Praise:

Rabbi Auschwitz is not so much a book about the historical Shoah as it is about the psyche of "a Jew who died fifty years too soon" and who now considers his pen "an oracular divining rod" that may or may not "stave off spiritual asphyxia." There's no question but that Louis Daniel Brodsky is haunted, his mind finding Shoah equivalents even in St. Louis crows eating carrion and in worms sliming across asphalt on a warm February day. He is "afflicted with living," as are the many survivors whose stories he enters. With his title character, "It's all about the darkness of the mantra/Which takes him away from himself," and as we listen to the best poems here and observe "toxic psychosis" that still desires a reason for being, we are appalled, complicit, nauseated, and gratefully ambivalent as we, by way of Brodsky's pounding and insistent voice, "survive forgetting" to remember.

— William Heyen, author of Shoah Train: Poems and finalist for the National Book Award

As the last survivors fade from us, Louis Daniel Brodsky summons up an extraordinary composite voice of "those afflicted with living amidst the still-smoldering ashes of the past." For many assimilated, "only in old age has it become imperative" like "a ghost still searching for a home" to meditate on the Holocaust. We're indebted to him for his imaginative feat, his nightmarish weave of anger, guilt and broken memory.

— Micheal O'Siadhail, author of The Gossamer Wall: Poems in Witness to the Holocaust and Globe

In Rabbi Auschwitz, I felt the omniprescence of human inhumanity. It was simultaneously profane. Profound. Penetrating. Phobic. The panoramic pathos was often overwhelming. Thanks for writing it.

— T.J. Birkenmeier, author of Shoe Town and The Head Jobs

Reviews:

Some wounds take long to heal, and some are more vicious about the process than others. Rabbi Auschwitz: Poems of the Shoah is a collection of poetry from Louis Daniel Brodsky, going after his own recovery with a good deal of venom about the world, to himself, and what has happened to his people. As poignant and thought provoking as it is entertaining, Rabbi Auschwitz is a strong pick for poetry collections.

— Midwest Book Review

The poems in Rabbi Auschwitz all have the vertiginous, off-balance quality of nightmares. The very title of the collection combines two violently antithetical ideas, creating an impression of something shameful and forbidden, in the yoking together of the image of a Jewish spiritual guide and teacher with that of a brutal, sadistic death camp. . . . This is very powerful stuff, offensive if coming from some shrill anti-Semite, but bitter and ironic coming from a Jewish poet.

— The Potomac

Louis Daniel Brodsky, a prolific and acclaimed poet and essayist, once again tackles the complex and conflicting issues of the Holocaust in his latest collection: Rabbi Auschwitz: Poems of the Shoah" (Time Being Books, $15.95). In his unique style, which combines rigorous intellect and knowledge with sensitivity and compassion, Brodsky grapples with his own rage and confusion as a member of the Jewish people, realizing that all of us are "survivors" of Adolf Hitler's demented and demonic dream not just to eradicate the Jews of Europe, but to kill every Jew on the face of the earth. . . . Each week, hundreds of the survivors of the Shoah, the last living eyewitnesses to the horrors of the death camps, die. Brodsky takes up their cause to use his considerable poetic skills to give voice to those who have passed away. . . . It has been said that such horrors occurred at Auschwitz, that there are no longer any songbirds on the blood-soaked ground where the death camp once stood. The image of the black crow, a sleek, highly intelligent and menacing bird still haunts Brodsky's psyche, just as it did in his earlier collection, "Gestapo Crows," as illustrated by his prefatory poem:

Bestial Desire

Instinct may hold the only clue

As to how crows, darting toward a flattened possum,

Then back to road's shoulder,

With beakfuls of bloody eye, entrails or tail,

Avoid obliteration by cars racing along the pavement,

But I'm not sure I trust my instincts

To extrapolate a facile answer

From my observation of the commonplace.

Doubtless, theirs is a practiced act of savagery,

A necessary balancing of symbiotic opposites —

Life rising out of life giving up.

It's nature insulating itself against decay,

The most common denominator in death's equation.

But perhaps these easy explanations

Fail to give the fanatical will to ravage its due.

Maybe it has as much to do with bestial desire.

Rabbi Auschwitz: Poems of the Shoah will become an important and enduring part of the literature of the Holocaust, and a copy should be on the shelves of readers of all backgrounds. It is an important and powerful statement by a gifted writer in our midst.

— St. Louis Jewish Light

L.D. Brodsky has published somewhere between sixty and seventy books, most of them poetry collections and a notable handful of these devoted to the Holocaust, including The Thorough Earth, Falling from Heaven, Gestapo Crows and The Eleventh Lost Tribe. Brodsky's emphasis, especially, in the later works, is on survivors and the children of survivors, in a contemporary setting, haunted by memory and imagination.

The poems in Rabbi Auschwitz all have the vertiginous, off-balance quality of nightmares. The very title of the collection combines two violently antithetical ideas, creating an impression of something shameful and forbidden, in the yoking together of the image of a Jewish spiritual guide and teacher with that of a brutal, sadistic death camp. The eponymous poem, like a number of others in the collection, takes place in a seedy St. Louis bar where the protagonist, "Rabbi Auschwitz," customarily ushers in the Jewish Sabbath on Friday night, drowning "in a Kaddish of white noise and crimson wine," trying to purge his memory. Other titles similarly suggest the surreal, nightmarish horror so prevalent in these poems: "The Pope Who Would be Fuhrer," "Cattle Drive to the Emerald City," "St. Patrick's Day Breakdown of a Refugee," "Flight to Hades." Others are less surreal but no less disturbing: "Blood Libel," "The Final Solution," "Nuremberg Lies."

Just as the Blood Libel itself partakes of folk legend, often Brodsky's poems employ the nightmare elements of fairy tales to make their point. "Black Forest Tales," for instance, begins: "Jack Speer and Jill Schwartz went up the hill,/To fetch a pail of racially mixed sex . . . " It continues later in the poem:

Sleeping Hebe Beauty and Cinder-and-ash-rella,

Where are you when the clock strikes midnight

And Prince Himmler strokes his Thuringer,

Heydrich pounds Goering’s bratwurst,

And the phantoms of the Grimm Third Reich brothers

Begin reciting tales of repressed kike maidens,

Exposing their own sexual frustrations,

Decadent peccadilloes, shitty political indiscretions?

This is very powerful stuff, offensive if coming from some shrill anti-Semite, but bitter and ironic coming from a Jewish poet.

The people that these poems concern themselves with are all haunted by survivor's guilt, survivor's remorse, "afflicted with living/Amidst the still-smoldering ashes of the past." ("Cattle Drive to the Emerald City") The poem "Green Peas" is especially heartbreaking, opening with an epigraph from a survivor named Elaine Dommange, as quoted in USA Today, so the reader knows right away this particular nightmarish scene is grounded in reality, that "in 1942/She was eight years old,/Eating green peas in her family home in Bordeaux, France" when the local police herded her family "to the gas chambers at Auschwitz,/Left her bereft, in a matter of seconds,/An orphan, one of an estimated 2500." As it happens, even fifty-five years later, in 1997, when she was interviewed, "this woman in her mid-sixties/Still can’t eat green peas,/Gets nauseated when she sees them on a plate." The ashes of the past, indeed.

Echoing his 1992 collection, Gestapo Crows, Brodsky frames this three-part collection between a prologue ("Bestial Desire") and an epilogue ("Crows' Convention") that focus on the image of the crow — that dark, strutting, foreboding scavenger, so like a ruthless uniformed stormtrooper, ending the collection on a cautionary note — for if it happened once, who’s to say it won’t again? Certainly not a Holocaust survivor: "You only think they only scavenge rabbits and squirrels."

— Main Street Rag

To read my interview with Charles Adès Fishman, about my writing on the Holocaust, please click here.

BUY THE BOOK from Amazon.com

Ghost Ship Over Poland

A hazy vapor hovers in his psyche's sky,

A dense heat inversion,

Thick with the stench of burning flesh,

Visible to his blind-drunk sight.

He's a patch-eyed pirate,

Who once defied Nazi vessels

On the high seas, just east of Eden,

Separating Nod from Terra Incognita.

Dead-end July's egregious heat

Turns his dreams from a Hades

Into a sun unfurling colossal flares

That scorch sleep, set his breathing aflame,

Reigniting bedsheets he's spent all night

Wrapping, like a shroud, about his body,

By now charred beyond identification

Even by his waking self.

He hovers in his defunct psyche,

Like hazy vapors in an Auschwitz sky

Perforated by the eyes of a million lost spirits

Who've risen or are just now rising

Through rumbling oven stacks —

Roman candles shooting clots of human ash.

Amidst this polluted dislocation, he sees himself,

A ghost still searching for a home.

No longer owning a living soul,

He boards his skull-and-crossbones ship

Bobbing in the hazy ocean above Poland,

Hoping to sail the open seas.

But he's been stalled here fifty years,

Waiting for a breath of fresh breeze

To billow his shroud-sheets,

Fill his incinerated spirit with the will to live.